Do You Know Top 23 Best Animated Short Films!

23rd Nov 2021, author: dreamengineanimationstudiomumbai

As you may be aware, animation is one of the most rapidly rising fields. And, as you may know, it was once only utilized in the entertainment business, but it is now employed in a variety of industries.

Animation has progressed significantly and is now quite advanced. It’s also causing a stir in the short film business.

We’ve compiled a list of the top 23 animated short films for you to enjoy.

“Storytime” (Terry Gilliam, 1968)

What exactly is it?

Those who are familiar with Terry Gilliam’s live-action films will notice a strong current of cartoonish mischief running through his films. People who have watched his work on Monty Python’s Flying Circus will not need convincing of his talent as an animator. Few of us are cognizant of the bunch of shorts he produced prior to actually leaving the United States for the United Kingdom, the best of which is “Storytime,” his debut. Dismiss the title: what happens in this film is almost incidental (if we tell you that the movie eventually resulted with the Three Wise Men getting chased through a sequence of Christmas cards, you’ll have the concept).

What’s the good thing about it?

The cheerfully irreverent approach to every aspect of the craft that distinguishes “Storytime”: a visual style develop from having to move cutouts; sketches connected around each other by only the freest stream-of-consciousness strands; self-referential intertitles which impolitely interrupt the narrative… In a nutshell, it’s Pythonesque humour well before Pythons. Humor will never be the same after that.

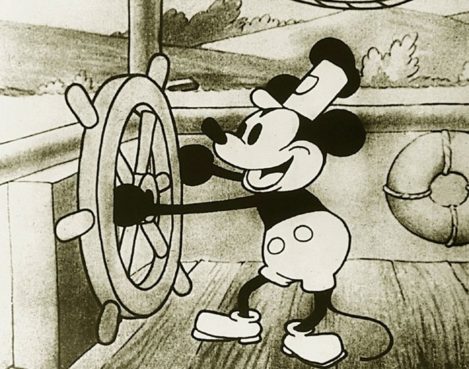

“Steamboat Willie” (Walt Disney, 1928)

What exactly is it?

Mickey Mouse was a modest sailor who lived in a globe where everybody was unfailingly peppy and everything was a potential musical instrument prior to actually acquiring vocal cords and becoming the biggest cultural touchstone on the planet. In the absence of dialogue or a compelling storyline, songs, playing drums, mooing, as well as a lot of toe-tapping—is what propels “Steamboat Willie” forward (it was the first cartoon to use fully synchronised sound). As a result, the seedlings for Disney’s catchy song-and-dance numbers were sown.

What’s the good thing about it?

Today, the portrayal of animal abuse in “Steamboat Willie” appears insensitive (animals are used as musical instruments). Even so, it is a seminal work that set the standard including everything from “Tom and Jerry” to “The Itchy & Scratchy Show” (He paid the debt of influence with a very funny parody). It also demonstrates that Uncle Walt was however the suave businessman from Saving Mr. Banks—he might draw as well.

“The Cat Came Back” (Cordell Barker, 1988)

What exactly is it?

A lonely old man receives undesired company inside the form of a cat who appears one day on his door – step and demonstrates to be as dangerous as it is cute. The movie retains its demonic sense of humour right up until the twist conclusion, that is captivated by the famous song of the same name, that also serves as a mocking refrain on the soundtrack.

What’s the good thing about it?

“The Cat Came Back” might refrain from breaking new ground, though it did dance on old ground with impeccable timing. As one would expect from a film based on a song, the majority of the humour stems from the use of music, beginning with the first scene, in which the old man plays a sousaphone, with many brass instruments. But to those who gag at the slightest sign of righteous, doe-eyed Disney living creatures, this same film’s feline star offers an excellent antidote.

Home on the Rails” (Paul Driessen, 1981)

What exactly is it?

A couple lives on the railroad tracks in a house. Despite the occasional interruptions of the passing train via their living room, those who live a serene domestic life; however, whenever the husband—a gold explorer in hard times, this same train takes on a more sinister significance.

What’s the good thing about it?

Dutch animator Paul Driessen is one of those animators who appear to also be known to only some animators, which is a great shame given how creative and worth watching his films are. After earning his streaks on projects such as Yellow Submarine, Driessen transitioned to solo projects, where he honed all his squiggly cartoony graphics and his quick witted storytelling technique. His films are rich in black humour, perhaps it’s nowhere more so in “Home on the Rails,” a marvellously wicked sketch of economic downturn that still rings true today.

“Bob’s Birthday” (Alison Snowden and David Fine, 1993)

What exactly is it?

“Bob’s Birthday” is possibly the funniest comic strip already known, a (quite literally) balls-out representation on middle-age anguish. Bob is a dental hygienist with a mundane existence and a bumbling wife who has quietly planned a surprise 40th birthday party for himself. Things go horribly wrong, but Bob is unaware of it.

What’s the good thing about it?

The film is so good that it won an Oscar and spawned an excellent four-season TV series, but it is still relatively unknown. The movie’s intended adult audience could struggle to accept how something so simple can lift off certain fine observational comedy. It’s their loss.

“Knick Knack” (John Lasseter, 1989)

What exactly is it?

Pixar’s fourth short is indeed a Chuck Jones–inspired comedy play about a snowman attempting to escape his planet and attain the sexy mermaid who lives next door. The movie was later released again in a censored version after being deemed too bisque for younger viewers.

What’s the good thing about it?

“Knick Knack” may appear to be a remnant of a bygone era, as it was created when Pixar was still a computer hardware company and perhaps the most renowned Buzz was Aldrin. Nonetheless, it did a huge amount to create computer animation as a valid art form. The adorable short film received widespread acclaim just at time, prompting one critiques to call director John Lasseter “the closest thing to God that has ever graced the electronic images community.” Now as the film’s technical prowess has faded into obscurity, what stands out is it’s own old-school allure: “Tom and Jerry” humour, a Looney Tunes–style getting smaller loop just at end, and Bobby McFerrin’s airy scat score.

“The Old Lady and the Pigeons” (Sylvain Chomet, 1998)

What exactly is it?

“The Old Lady and the Pigeons” is a stylistic tour de force, an acerbic ode to Jacques Tati–style pantomime, as well as a clear indication also that French are competent of twisted humour each tad as black as the darkest. The It’s Always Sunny throughout Philadelphia parody. A poor and hungry cop disguises himself as a bird in an attempt to fool an elderly lady into trying to feed him. Failures occur, and they go really quiet, very wrong.

What’s the good thing about it?

French filmmaker Sylvain Chomet arranged out almost all the tropes which repeat in his feature movies, again from Oscar-nominated The Triplets of Belleville towards the special concert testing Attila Marcel, in just this bonkers 22-minute debut. The French animator’s cartoonish style, as well as his unnerving wit and odd fascination with fat people, are all perfect the way. The storey falls short, like it does in all of Chomet’s works, however for a film that contains more thoughts than a brainstorming process with Thomas Edison, that’s to be expected.

“The Wrong Trousers” (Nick Park, 1993)

What exactly is it?

“The Wrong Trousers,” a tale of criminal justice, brilliance and craziness, dogs and precious gems, cheese and crackers, was without a wonder the zenith of Aardman Studios’ output, and that is a very high pinnacle indeed. This is 30 minutes of pure, unadulterated joy, as imaginative as Charlie Chaplin, as parched as Buster Keaton, as crazy as the Pythons, as cosy as the Muppets, but as interesting as Indiana Jones.

What’s the good thing about it?

Everything on the list above. “The Wrong Trousers” was not Aardman’s 1st Oscar winner (that honour went to “Creature Comforts”), nor was it the studio’s first Wallace and Gromit storey (that honour went to “A Grand Day Out”). But in this case, everything just clicked into place, resulting in a task of popular art that really is, for all manner of reasons, flawless. So that has to be reason to rejoice.

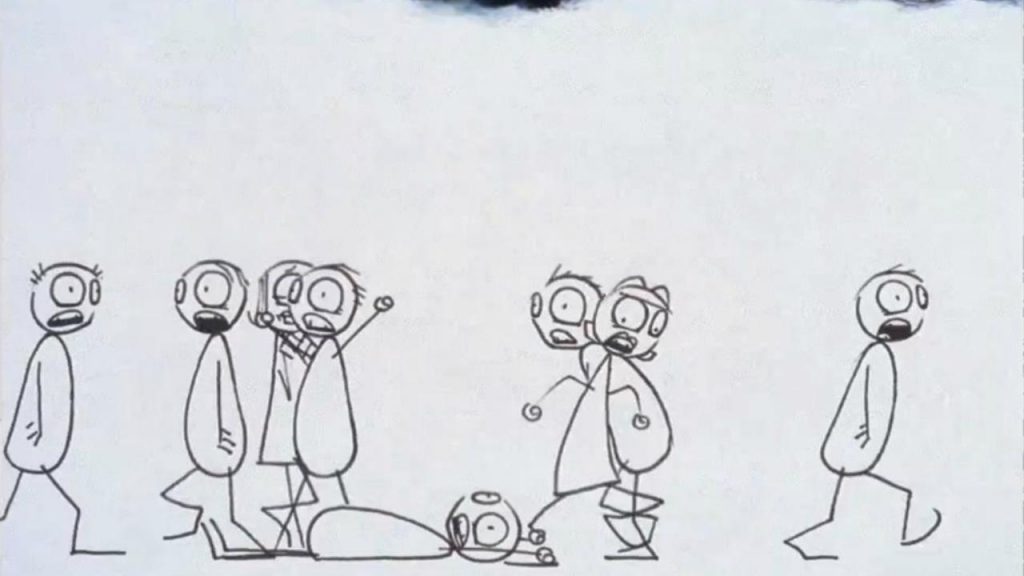

The Meaning of Life” (Don Hertzfeldt, 2005)

What exactly is it?

This is DIY writer, animator, director and genius Don Hertzfeldt’s tries, as the title suggests, to get it to the base of what is heading on and in our world in about 12 minutes. His results could be amusingly obscure—decay, gossip, Life, death, aliens, madness, genetics, and also the vastness of production all play a role—but it’s difficult to avoid the impression that Hertzfeldt is aware of something we don’t.

What’s the good thing about it?

It demonstrates that anything is possible in animation: With the exception of a few voices (and a triumphant classical soundtrack), “The Meaning of Life” was created entirely by one man without the use of a computer. Nonetheless, this is indeed a movie that spans time and space, delves deeply into the essence of life, and produces both frightening facts but almost unexplainable beauty. When his first feature movie, It’s Such a Beautiful Day, was released, one critic particularly compared Hertzfeldt from Terrence Malick and Stanley Kubrick, which are entirely appropriate comparisons.

“The Hand” (Jirí Trnka, 1965)

What exactly is it?

In Jir Trnka’s final and biggest work, “The Hand,” state subjugation of the artist is literally represented as a gigantic gloved hand (the inspiration for the final boss throughout Super Smash Bros.?) pestering a hapless sculptor, ultimately going to drive him to suicide.

What’s the good thing about it?

Trnka has been termed “the Walt Disney of Eastern Europe” due to his massive influence on Soviet animation. This same parallels end there—unlikely it’s that Disney would ever have to contend with malevolent state censor board there was no attempting to deny Trnka’s influence on generation to generation of animators, which include Jan svankmajer, whose satirical humour and the use of puppets obviously owe much to his predecessor. “The Hand” exemplifies both animation and filmmaking at their most playful and bitter.

“Where Is Mama?” (Te Wei, 1960)

What exactly is it?

Here on exterior, it is a movie about a swarm of toads on their way to find their mother frog, having encountered a colourful cast of sea organisms along the way. Undoubtedly, provided that it was made in Mao’s China, it also serves as a learning experience in civil society cooperation and state intervention.

What’s the good thing about it?

“Where Is Mama?”, more than almost any other film on this list, is a reflection of the times and location: The sickeningly chirpy woman voiceover and translucent agitprop portray Maoist art’s worst tendencies, as well as the boundary about needing to protect all plants from insects is assured to raise eyebrows. Nonetheless, the film transcends its political context thanks to The Wei’s solid understanding of Chinese artistic traditions (particularly the watercolour technique of painter Qi Baishi). Turn off from the audio and marvel at the magnificent animation—it defies the concept that Mao’s regime spelled the end of great art.

“Tale of Tales” (Yuri Norstein, 1979)

What exactly is it?

Yuri Norstein, a Russian filmmaker, returns to his favourite theme as to how we encounter our possessive memories, particularly those of early life, inside an imagistic autobiographical art college. We observe the start of the war as well as Norstein’s alcoholic father’s mistreatment, whereas other chapters defy problems that can be avoided.

What’s the good thing about it?

There is an everlasting stereotypical image of Soviet animation as abstract and infuriatingly obtuse, as a perfect Simpsons series once demonstrated. On the first viewing, “Tale of Tales” does nothing to dispel that notion—film, Norstein’s which is preoccupied with the framework of memory above all, is narrative form internally inconsistent and drenched in symbolism. Nonetheless, its common themes make sure that it will attack a current install with anybody who sees it: this is really a film which has crowned innumerable polls, and it influenced British animated film specialist Clare Kitson to learn Russian in order to publish a book about it.It’s a perplexing, piercingly beautiful work that, sadly, has yet to receive a sequel (Norstein, now and in his seventies and a notorious high achiever, has been working on an acclimation of Gogol’s “The Overcoat” since 1981).

“The Street” (Caroline Leaf, 1976)”

What exactly is it?

“We didn’t leave the city the summer my grandmother was supposed to die—or, even though my mom put it, ‘pass away.’” “The Street,” an ability to adapt Mordecai Richler’s story “, unveils as a study rooms of death in a nearer Canadian Jewish community from such a pithy opening line. The kids’ lighthearted reactions and wry humour help to lighten the mood.

What’s the good thing about it?

Bambi’s mom was not the only death in animation, as Caroline Leaf’s work of art, by having to confront this the most significant of subject areas with wit and candour, seems to be another warning that animation can handle serious themes with the maturity of live action. Together with Aleksandr Petrov’s “The Old Man and the Sea,” it’s really a good demonstration of the notoriously difficult paint-on-glass technique, as well as a wonderful exercise in color—all tea-brown hues with the occasional splattering of orange. Another win for the National Film Board of Canada, for whom the films appear prominently on this list.

“The Man Who Planted Trees” (Frédéric Back, 1987)

What exactly is it?

“The Man Who Planted Trees,” an ability to adapt a Jean Giono story, tells a story of a lone shepherd’s effort to reforest a forlorn valley within the Alps on his own. The straightforward allusion of desperate love for eternal life is tried in Frédéric Back’s campaign logo impressionist movement, in which successive sequences morph into one another instead of conventional editing.

What’s the good thing about it?

Once Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies) completed his latest film in December 2013, his 1st action would have been to screen it for Back—and not a moment sooner, because the Canadian master passed away a few days later. The anecdotal example demonstrates how highly regarded he was by the animation community. “The Man Who Planted Trees” is his crowning achievement, a poll-topper that swept up prizes (including an Oscar) upon its original release. Back’s reputation is enclosed with this most soft of films, just as the shepherd’s spirit lives on in the forest.

“The Old Man and the Sea” (Aleksandr Petrov, 1999)

What exactly is it?

If “The Old Man and the Sea” appears at points of time to just be an animated film of those lame mega budget nature documentaries which used to be shown in IMAX theatres, it’s partially since it is an IMAX film—the 1st animation to be released on that massive screen, in fact. The movie, meant as a showcase for the then-new tech, plays Hemingway’s well-known tale very secure; it borders on schmaltz in locations, and the sound design is as durable as the wall surfaces of the aged man’s cabin.

What’s the good thing about it?

The animation is breathtaking—as simple as that. Aleksandr Petrov, a Russian animator, is among the few artists who has perfected the paint-on-glass method (also see Caroline Leaf’s “The Street”), and now here he uses it to its comprehensive significant direct and indirect, alternating between realist animal portraits and imagistic scenes with spine-tingling ease. The arm-wrestling scene is among the most light – filled action scenes in all animation.

“The Village” (Mark Baker, 1993)

What exactly is it?

Ants work together, whereas humans lie, fight and argue, and steal. That’s the implicit theme of Mark Baker’s sociopathic masterpiece, that also narrates the tale of an unconnected English village. Two villagers attempt to have an affair and yet are thwarted by their nosy neighbours’ interference. Suspicion leads to fighting, and then to murder.

What’s the good thing about it?

“The Village” is cited as an example of Britain animation’s golden period in the 1990s, and it’s easy and that’s why critical reflection was at it’s best comedy and most sneaky. The protagonists engage in all manner of sinful behaviour, from thievery to adultery, against the immutable backdrop of the church premises. Even the reverend is inebriated. The confined layout of the village, of the kind that Baker based on the design of the Theater, adds to the suffocation. The satire in the film is never hammered home.

“When the Day Breaks” (Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby, 1999)

What exactly is it?

In this lovely investigation of metropolitan disaffection, an unintentional death sparks a quiet identity crisis among some of the residents of an unnamed metropolis. The reality that all of us are an animal tends to make it all the more impactful (it reminds us of Spike Jonze’s video for Ridiculous Punk’s “Da Funk”).

What’s the good thing about it?

“When the Day Breaks” exemplifies the marvels which can be achieved when advanced methods are being used to start creating a vintage aesthetic. Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby from Canada go for the layered finish by drawing directly onto paper copies, resulting in a gentle, blurry style unlike any other. However, the film is more than just impressive visual effects. It’s also a relaxation technique on the irony of urban life, in which everyone is connected but no one speaks to one another—not your pretty standard subject material for an animated feature.

“Duck Amuck” (Chuck Jones, 1953)

What exactly is it?

“Duck Amuck,” a film in which meta meets forefront, is one of only two items on our ranking that really is truly regarding animation (see also “La Linea 1”). It begins with Daffy Duck dressed as a musketeer, acting out a swashbuckling scene against a fairy-tale backdrop. The scenery mysteriously disappears completely, plunging Daffy into a series of battles with none other than this same animator himself. So over the course of six unnerving minutes, Daffy is wiped away, drawn up, tried to drag through all sorts of bizarre landscapes, and even at one point physically attacked by the frame’s edges.

What’s the good thing about it?

Chuck Jones, the mastermind behind Warner Bros., had the brilliant idea of incorporating perspectives on the relationship among cinema and “reality”—normally the domain of beardy theorists—into a wildly amusing short starring a few of the studio’s best-loved characters. Clear evidence that exploratory filmmaking does not have to be dull.

“Father and Daughter” (Michael Dudok de Wit, 2000)

What exactly is it?

Michael Dudok de Wit’s Oscar-winning short utilises a monochromatic colour range and eight mins of dialogue-free time to tell a storey that might satisfy an entire motion picture. A dad and his daughter ride their bikes from across Dutch flats before he suddenly bids her goodbye by the sea as well as rows off into the location, never to be seen again. Nonetheless, as the girl grows older and ultimately quiets into old age, she returns to the location where they parted in the hope of seeing him again.

What’s the good thing about it?

The film’s main accomplishment is to convey a lifetime of longing through a simple, moving cyclical story. The daughter’s trips to the beach recur, like the having turned of her tyres and the waltz of the theme song. Decades go by. However, as the vague ending implies, time goes in circles, and death may not be the end. For once, the adjective Zen is appropriate—Dudok de Wit’s brushstrokes are undeniably influenced by Japanese painting. (Disclosure: the writer’s dad is Michael Dudok de Wit.)

“Pas de Deux” (Norman McLaren, 1968)

What exactly is it?

Norman McLaren’s “Pas de Deux,” generally regarded as that of the Scottish artist’s finest work again for the prolific Motion Picture Board of Canada, stands tall at the nexus of action scenes and visual effects. McLaren filmed white-clad dancing against a dark background, then conned the footage with an electro – optic printing to create psychedelic visuals, nearly stroboscopic visual effects.

What’s the good thing about it?

Everything works so well together: the jarring monochrome, the liquid ballet, this same illusion of an endless universe, the orchestral chord progressions which seem to go on everlastingly… McLaren was a fidgety empiricist who took an interest in a variety of techniques over the course of his long career, but he never produced animation as moving and elegant as this.

“Damon the Mower” (George Dunning, 1972)

What is it?

A tabletop is covered in card stock. Drawings influenced by Andrew Marvell’s poetry “The Mower’s Song” come to life on its exterior. The stanza was originally supposed to be read aloud by a storyteller, but Dunning cut the voice work in post – production.

What’s the good thing about it?

Dunning was a major player in the avant-garde animation scene before being hired to guide the trippy love-it-or-hate-it Beatles film Yellow Submarine. Luckily, his big-budget adventures did not straighten out his experimental bent. The proof is in this lovely short, which is too rarely seen nowadays but was groundbreaking at the time. Dunning translates Marvell’s poem about just a lovelorn mower in to the simplistic, almost abstract graphics, exposing the animator’s basic framework: pencil lines slithering across paper. The effect is hypnotic.

“La Linea 1” (Osvaldo Cavandoli, 1971)

What exactly is it?

Originally commissioned as just an ad for Lagostina kitchenware (no, we might not get it either), “La Linea 1” follows a gobbledegook human looking overview as he strolls across a single direction of so he is a part. When he comes across a stumbling block, he yells at the animation studio, who rapidly gets involved with his massive pencil. The film was a success, and it spawned a long-running television series.

What’s the good thing about it?

“La Linea 1” may not appear to be much, but still it packs more fantasy and kooky humour into its brief runtime than so many blockbuster movies do in 2 hours. This same film, like “Duck Amuck,” calls attention to its artifice in an amusing manner, coming across as a knowledgeable cross between such a piece of Abstract Expressionism and an incident of Pingu (the same character gave it a lead voice). If you enjoy it, there really are 89 episodes on the way.

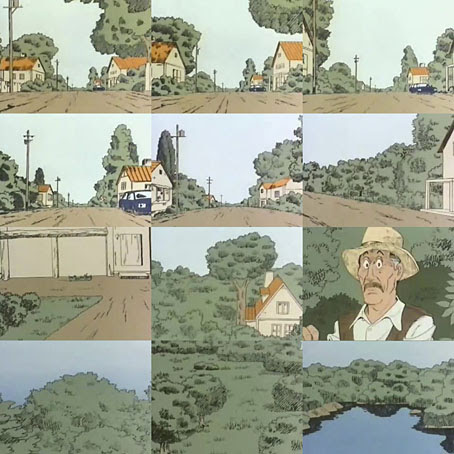

“Jumping” (Osamu Tezuka, 1984)

What exactly is it?

We take the first-person perspective of a young boy who explores how he has the ability to jump extremely high. He begins by bouncing around his neighbourhood, but just before lengthy he’s on a board games tour of the globe, having witnessed industrialization and wars in full swing before basically going to hell and back.

What’s the good thing about it?

Cartoonist, animator, activist, and medical doctor (yes, really) Osamu Tezuka is willing to take responsibility with some of the most playful and inventive anime ever made, and he is overshadowed by Studio Ghibli somewhere else. Exhibit A is this fantastic episode from his “13 Experimental Films” series. The ideological underlying message is strong—without stretching the metaphor so far, the film could be interpreted as a commentary on the social displacement felt by many Japanese following the fall of nazism. In the meantime, the cartoonish graphics obscure some really sophisticated experiments with point of view (with no CGI to fall back on!). It’s no surprise that “Jumping” jumped to award success.

If you are looking for the best national and international short films read this blogs on “Top 10 International Short Films, Probably you Don’t Know!” and “Are you in the mood to watch the top Indian short Films?” by Dream Engine Animation Studio, Mumbai.